- Home

- Susan Oleksiw

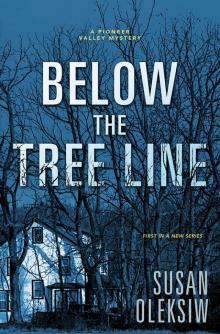

Below the Tree Line

Below the Tree Line Read online

Copyright Information

Below the Tree Line: A Pioneer Valley Mystery © 2018 by Susan Oleksiw.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any matter whatsoever, including Internet usage, without written permission from Midnight Ink, except in the form of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

As the purchaser of this ebook, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. The text may not be otherwise reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or recorded on any other storage device in any form or by any means.

Any unauthorized usage of the text without express written permission of the publisher is a violation of the author’s copyright and is illegal and punishable by law.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

First e-book edition © 2018

E-book ISBN: 9780738759272

Book format by Bob Gaul

Cover design by Shira Atakpu

Midnight Ink is an imprint of Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Oleksiw, Susan, author.

Title: Below the tree line / Susan Oleksiw.

Description: First edition. | Woodbury, Minnesota: Midnight Ink, [2018] |

Series: A pioneer valley mystery; #1

Identifiers: LCCN 2018016325 (print) | LCCN 2018020034 (ebook) | ISBN

9780738759272 (ebook) | ISBN 9780738758916 (alk. paper)

Subjects: | GSAFD: Mystery fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3565.L42 (ebook) | LCC PS3565.L42 B45 2018 (print) |

DDC 813/.54—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018016325

Midnight Ink does not participate in, endorse, or have any authority or responsibility concerning private business arrangements between our authors and the public.

Any Internet references contained in this work are current at publication time, but the publisher cannot guarantee that a specific reference will continue or be maintained. Please refer to the publisher’s website for links to current author websites.

Midnight Ink

Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

2143 Wooddale Drive

Woodbury, MN 55125

www.midnightinkbooks.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

For my parents

One

On the third night Felicity lifted the shotgun from its place in the cabinet, and this time she loaded it. Uncertain if she’d heard anything on the first night, she’d come down the stairs of the old farmhouse one step at a time and walked carefully through the front room and on into the kitchen, listening and wondering if she’d imagined the sound of activity outside. At first she’d told herself it was nothing, just animals scratching around, perhaps a skunk, or mice fleeing an owl. Perhaps it was just a gust of wintery air rattling an old sash window. She’d peered through the glass panes, scanning the side yard by the kitchen. It was too early in the year for a curious bear, and she’d never known moose to wander so close to the house. Perhaps it was nothing more than raccoons trying to get into the storage shed, or coyotes circling the barn where the sheep dozed. It might even be a dog enjoying a night off-leash.

But she knew sounds and smells, and something had told her this was different. By the second night she’d been sure of it, for two reasons. The persistence of the noise, for one thing. And the consistency of the hour, for another. It might only be reckless kids, but she didn’t dare ignore whatever it was. On the third night, she set aside her doubts and slept fitfully in a chair in the living room, dozing and waking. If there was something to discover, she would do so tonight.

And then, just before two o’clock, she heard the noise she’d been waiting for and hoping wouldn’t come. She slipped in the shotgun shells, hearing the familiar clicking sound like cutlery sliding into a drawer or a screwdriver tapping on a car engine. She locked the cabinet and eased open the front door.

The porch ran the length of the small house. From her spot in the dark doorway she could see well enough by moonlight to study the ground immediately in front of her. She’d left her gloves inside, but she felt warm with her boots and flannel shirt and jeans. She scanned the ragged lawn for footprints in the hoar frost. Across the dirt driveway and beyond the fencing lay a field open to the night sky. She waited for a shadow to separate from a fence post, or rise up from the covering on the vegetable garden. But when all remained still, she stepped off the porch. She turned to her left, toward the barn. Not a sound of distress reached her. Whatever it was hadn’t alarmed the sheep. If it had been a predator, she would have heard them stamping and bumping each other, and whining, frightened by the smell. But they slept, quiet and still.

She walked to the corner of the house, where she strained for a sound to guide her. A tree branch rustled in a windless moment and she lifted the shotgun and stepped along the side of the house. She took each step consciously, waiting and listening. As she passed in front of a window, she placed her foot on the ground. Here it was soft, partly thawed where she had cleared away debris, exposing the stone foundation to the heat of the sun. She’d forgotten about the rake she had left leaning against the shingles earlier in the day. Her foot on the softened earth was enough to sink the soil and jostle the rake; it clattered along the shingles as it slid down. She held her breath. The birds fell silent.

From behind the house came the rustling and tearing of branches. She bolted the few steps into the back yard, lifted the shotgun, and fired into the air, shooting over the twisted black branches of the old, abandoned apple trees. She didn’t want to hit an unknown creature or person but she did want to scare off whatever or whoever it was.

Gradually the silence returned. The ground around one pole for the laundry line looked freshly torn up, as though two people had scuffled there, close to the old foundation. Felicity felt a rush of adrenaline. She’d thought of one person, never more than one. She tamped down a flash of fear and walked deeper into the orchard. In the dim moonlight draping the old fruit trees she traced a path through trampled ground leading away from the back of the house and into the woods. Ahead she could hear the indistinct sound of motion among trees, and then the night was still. She thought about following but she didn’t have enough light for tracking at this hour. And she wasn’t sure what she’d do if she caught whoever or whatever it was either. She’d have to leave that to Kevin Algren, the chief of police. She’d call him in the morning.

The little she could see told her whoever it was had been working along the back of the house. She headed to the side and inspected the ground around the bulkhead near the kitchen door. If someone was trying to get into the house, coming in through the cellar would make sense. But the area looked undisturbed. She returned to the other side of the house and picked up the rake. She kicked herself for not putting it away earlier. That tiny sound had given her away.

She walked over to the shed, which was in fact an old tack room added to the barn in her grandfather’s day. He’d kept a few horses and wanted a place for saddles and bridles. Most of that was gone now, and Felicity used it for tools. If the intruder had gone for the tool shed, that would have made sense. She kept some of her better tools out here in warmer weather and moved them indoors when it got cold. She checked the latch on the shed, pulled. She shone her flashlight on the ground. But there was no si

gn anyone had tried to get in.

Maybe it was kids after all, too young to know that tools in the shed were valuable and could be pawned, the bulkhead had almost no security, and trying to dig through a crumbling foundation would never work. But anyone who knew anything about Tall Tree Farm knew she didn’t have anything worth stealing except the tools. Neither did anyone else in West Woodbury. This part of Pioneer Valley might be beautiful, but it was a forgotten corner of rural America, a land prosperity had abandoned, choosing instead to follow the turnpike farther south.

Felicity walked back to the front of the house, making a mental list of what she’d have to do to put up motion detector lights on the back. She had them for the barn, but not the house, and that would have to change. She turned for one last look at the back yard and the old orchard.

“Next time,” she whispered into the night, “you won’t be so lucky.”

Two

Felicity swung the pitchfork up and over her shoulder and heard the satisfying thump of soiled straw hitting the wheelbarrow behind her. It rocked on its rusty legs. She finished mucking out the stall and laid down a fresh bed of straw. When she’d first agreed to take on the three Merino sheep for local fiber artists, she hadn’t given much thought to the extra work. She was used to work. But she hadn’t cared for animals for a number of years, not since her dad had given in to medical problems and sold or gave away the few they had. And once he’d moved to the Pasquanata Community Home, she was too busy focusing on timbering and the vegetable garden to think about acquiring any animals.

She’d quickly adapted her life to caring for the sheep, and she’d begun to enjoy them. They nibbled at her shoes and rubbed their noses against her jeans, and their growing coats made them look like tubby toys. She stabbed the pitchfork into the fresh straw, breaking it up and spreading it around. Through the cracks in the old barn wall, light washed over the new bedding and lit up the dust rising into the air. She sneezed.

“Gesundheit.”

Felicity backed out of the stall and turned to the barn door. “I didn’t hear you drive up. How long have you been there?”

“Just got here.”

She tossed the last of the soiled straw into the wheelbarrow, hung up the pitchfork, and maneuvered the wheelbarrow through the barn door and around the back. A moment later she returned to the front, where Jeremy Colson leaned against his truck, his arms resting on the hood and his feet crossed at the ankles. The morning sun glinted on his brown hair, turning it golden, and Felicity noted that in this light she couldn’t see the gray hairs growing in at his temple.

“I love watching you work,” he said. “Especially when you sing to yourself.”

Felicity had known Jeremy her entire life, and they’d been partners since his marriage fell apart, when his wife ran off with another man, leaving him to raise his little girl alone. That was over fifteen years ago.

“So? I can enjoy myself, can’t I?”

“I still can’t believe you took them on.” His blue eyes twinkled with amusement.

Felicity followed his glance to the sheep in a small fenced field. “I think they’re kinda cute.” She laughed. “Besides, you know I only say that because they’re not mine. If anything happens to any of them, I just get on that phone and I call the artists’ co-op and I say heya, folks, your sheep need to see the vet. And they come running over like someone sighted Michael Jackson in the apple orchard.” She rested her hands on her hips and smiled. She was tall and slim, and wisps of dark brown hair loosened from her ponytail floated around her cheeks.

“Speaking of your orchard,” Jeremy said.

“What about it?”

“You called Kevin Algren at five thirty this morning. What’s this about someone trying to get into the house last night? Or maybe early this morning?”

“I was wondering why you were over here so early. You’re working over near the Durston line, aren’t you?” Jeremy owned a construction company, building new homes or other small or mid-sized projects. “Come on.” Felicity waved to him to follow her. “I’ll show you.” She led the way around the barn to the back of the house. The morning sun had warmed the earth and any sign of frost had evaporated, but the ground was still torn up around the laundry pole. “It looks like people were fighting here.”

Jeremy knelt down, looking along the old stone foundation and around the yard. “Well, the ground sure is churned up.” He stood. “Interesting how much it’s thawed, and so early. Kevin said you took a shot at someone, maybe two people.”

“I shot high, over the trees in the orchard. I could hear something moving but I couldn’t see clearly.” She stepped toward the crumbling stone wall that once encircled the old orchard and pointed to the flattened grass. She cut the grass in the area only twice a year, once in the early spring and again in the late fall. Otherwise it grew as it wanted. She brought the sheep here once in a while and they seemed to keep it mostly in trim.

“You said it might have been one or two.”

“I don’t know how many, if it was just one or two. I’m not even sure it was a person.”

“But you think it was.”

Felicity rested her hands on her hips and gazed into the woods. “I do.” She turned to look directly at him. “And so does Kevin or he wouldn’t have called you. Did he call you as a friend or as an auxiliary cop?”

Jeremy shrugged. “He didn’t say.”

He walked into the orchard, following the path made just a few hours earlier, the matted grass slow to spring back in the late winter chill. Even though it had been an unseasonably warm winter, the earth resisted being hurried into spring. He held up a branch as he stepped into the woods, onto ground covered in debris instead of trampled grass.

“Lots of broken twigs,” Felicity said, coming up behind him, “but nothing useful like a snagged scarf or a pair of gloves. I tried to follow the trail, such as it is, but I couldn’t tell which way they went.”

“You didn’t find any tools they left behind?”

Felicity laughed. “It’s not funny, I know. They do seem incompetent. Three tries and nothing to show for it.” She grew serious. “The persistence alone is troubling, but it wouldn’t take much to get into the house. The locks are old and I probably didn’t even lock the kitchen door the first couple of nights. But what could they want?” She led the way back to the yard.

“It looks like they thought you had a cellar they could get into.” Jeremy walked over to his truck.

“Then why didn’t they go to the bulkhead, at the side?”

“Can’t tell you that, Lissie. But Mom sent you something.”

“Loretta?” Felicity frowned, her gray eyes shedding their sparkle. She liked Jeremy’s mom, a lot. Never afraid to say what she thought, Loretta showed no signs of aging gracefully, or at all.

“The last time she went over to the shelter to volunteer, a few days ago, she came home with a dog to foster. And she thinks this one would be right for you. I told her you have a cat.”

“Miss Anthropy can handle any dog of any size.” As if in response to her name, a calico cat curled up on the porch lifted her head, flicked her tail, and resettled herself. Felicity looked into the cab of the truck. “So even though Kevin thinks this is nothing serious to worry about, just the random animal digging in my yard, he called you and you called Loretta and she suggested a dog?”

“Something like that.”

“You’re feeling guilty, aren’t you? Like you should have been here.”

Jeremy rested his hands on his hips, then put an arm around her and kissed her. “We’ve talked about this six ways to Sunday. Someday we’ll have to make a decision.”

Felicity nodded and ran her hand over his back before turning to the truck. “Is it the little Lab that Loretta was thinking of giving your daughter when she graduates from college next year?”

“Mom told me she t

hought you should have a dog right now—after she gave me a piece of her mind for leaving you alone out here.”

Felicity looked back at the house, then at the sheep in the paddock beyond the barn. “I kept telling myself it was nothing, but I was watching myself take down the shotgun and load it, all the while thinking it’s nothing, just an animal. But it wasn’t. I know it wasn’t. I just can’t figure out what they—he or she or whoever—wanted.”

“You may have scared them off with firing at them.” Jeremy walked to the back of the truck and dropped the tailgate. He drove a white Ford F-150, which he traded in every two years. His construction business was hard on vehicles, he said, but Felicity knew he hated driving around in old rattletrap trucks, as he had for years when he was younger. And as she did now. Her Toyota always looked pathetic next to his Ford. He kept it clean and shiny, the better to highlight his company name, Colson Construction. He pulled the dog crate closer to the edge.

“Is there anything special I should know about the animal?”

Jeremy shook his head. “Forty pounds of love and affection.”

“So where is this dog?”

“He’s in there somewhere.” Jeremy unlatched the crate door. Instead of jumping down and rushing to freedom, the small black Lab stared at him with worried eyes.

“Oh dear.” Felicity peered in at the animal. “Why me?”

“Loretta says you’re patient and the dog needs patience. Besides, this is what she had and she doesn’t trust you to go get one even though it would be a good idea.”

“So then I’d have two dogs.”

“Not a bad idea.”

Felicity and Jeremy continued to look in at the animal, which seemed to retreat deeper into the crate.

“What’s his name?”

“Shadow.”

“Hmm. What happened to him?” Felicity bent over to get a better look at his floppy but slashed ears.

“Not sure, but it looks like he was meant for dog fighting.” Jeremy didn’t try to hide the disgust he felt about this. He’d helped his dad with the dairy farm from an early age, and Felicity knew he was exceedingly gentle with animals. After his father died, Jeremy let the dairy business go, but he kept a small herd of dry cows because he liked having them around.

Below the Tree Line

Below the Tree Line